Let me knock on the fourth wall for just a moment and welcome you, reader, to a new Foodseum serial, The Test. Each month, I’ll be taking an analytical approach to recipe development, picking dishes apart and putting them back together, resulting in new and exciting ways to enjoy everyday favorites.

We begin this month by recounting my experience competing in Culinary Fight Club, a for-charity, monthly competition that pits three Chicago chefs against each other in a themed, one-hour culinary throw down. With temperatures relentlessly plummeting, it was only appropriate that we would be tested on a cold weather staple: chili.

Give All You’ve Got to the Chili Pot

What had started as a fairly casual night of friendly competition was beginning to bear down pretty heavily on my shoulders as time raced off of the clock.

“Five minutes, chefs! Five minutes!”

Roars from the crowd, music pounding through the bar speakers, and the emcee’s shouted encouragement through the megaphone all melted into white noise; it was now or never, this chili had to be finished if we had any hope of clenching first place. I shot a passing glance at my sous chef, who was working just as furiously to make it in under the time limit. We could do this.

But.

Allow me to budge you back from the edge of your seat -we didn’t win. We landed third place. Out of three people. I will say this up front: I had such an amazing time, and we were competing against two very deserving guys with fantastic teams behind them. Although, this experience begs the question, what would it take to have made our chili into first prize material?

Reinventing the Meal

Walking into this challenge, I was adamant to rework the idea of a chili. At the same time I set out to preserve the identity the dish; a thick, richly flavored meat and pepper stew with beans and tomatoes. A week before the event, the chefs were allowed to view the pantry items that we would compete for (in one 60-second mad grab), and there were three must-haves: poblano peppers, fresh tomatoes, and good old kidney beans.

Culinary Fight Club allows its competing chefs to bring three secret ingredients, so that each chef can put his or her personal touch on their recipe. It was here that I would throw my curveballs; smoky bacon, hard apple cider, and Dijon mustard would push the traditional boundaries of the dish, and gain me a creative advantage.

Award-winning chilis are usually allowed to have their flavors melded together over long periods of time (think up of eight hours) before they’re even deemed worthy to serve. So with 60-minutes on the clock, I would have to bust out some serious shortcuts to achieve big flavor.

What I hoped to accomplish was simple: fire-roast my vegetables to add a hint of smoke and accentuate natural sugars, cook everything in the bacon fat, and reduce it all in apple cider to bring a further hint of sweetness to the mix. I would finish it all off with more apple cider and the Dijon mustard, channeling great French chefs before me, who would finish certain pan sauces in the same way (although they were slinging wine in place of my cider).

A wonderful plan, and it worked beautifully, all until a mere thirty seconds remained on that infernal timer. With the crowd counting down, I knew I was in trouble. My chili was no chili; it hadn't reduced past a soup consistency.

I didn’t even need to hear the judges’ comments to know I had shot myself in the foot. Although I wouldn’t be winning a chili competition with a soup, across the board my dish was praised for both it’s complexity of flavor and creativity. This lit a fire under me; I didn’t want to give up on what was fundamentally a great dish. I would roll up my sleeves one more time and get it right.

Itchin’ To Get It Right In The Test Kitchen

I’m no food scientist, but I know the best way to approach improving recipes is by treating it as an experiment. My recipe I presented to the judges is my control, and the various ways I could have feasibly thickened my chili with available ingredients are my variables. Simply making a large batch of chili (or soup, whatever), splitting it, and trying each thickening method would allow me to find the best solution.

Again, there are many ways to thicken a liquid, but let’s look at what was available to me at the time:

Variable 1: Tomatoes

Large cans of both diced and crushed tomatoes had been available in the pantry, and are both quick ways to add body to a stew. Unfortunately, they were no good to me; by the time I added enough to achieve a proper consistency, the flavor profile would be dominated by blasts of concentrated tomato flavor. Any enhancements I achieved by fire-roasting my fresh tomatoes would be totally whitewashed by the heavy flavors of their canned cousins.

Variable 2: Beans

It was highly possible my answer laid hidden in the kidney beans I nabbed from the pantry, and this had in fact been my original plan for adding body to my cooking liquid, until time ran out. Adding a purée of beans or starchy vegetables to a dish is one of the oldest methods for thickening; but would it be the most effective?

Rinsed beans fresh from a can (a conflicting description if there ever was one) have indeed been cooked, but are still slightly difficult to mash. Letting them soak in the pot isn’t ideal, because then you’ll spend all day separating them back from the rest of the ingredients. Instead, I reserved a portion of beans in a separate bowl and ladled hot broth from the pot over them.

Five minutes later they were much easier to mash with the tines of a fork, transforming them into…well, a rather unattractive mass. Stirring my purée in and bringing it to a boil did indeed add noticeable body, but also left a lightly gritty texture and an overly cloudy look to the liquid. Palatable, but far from ideal; one last ingredient remained, and I had high hopes for the results.

Variable 3: Flour

I hadn’t planned on seeing flour on the pantry table, but any chef could tell you why it was a welcome sight. When combined with fat at the beginning of the cooking process, it forms the magical paste we call roux, a highly effective thickening agent. But what if you miss that window and find yourself at the end of a dish that’s crying out for body?

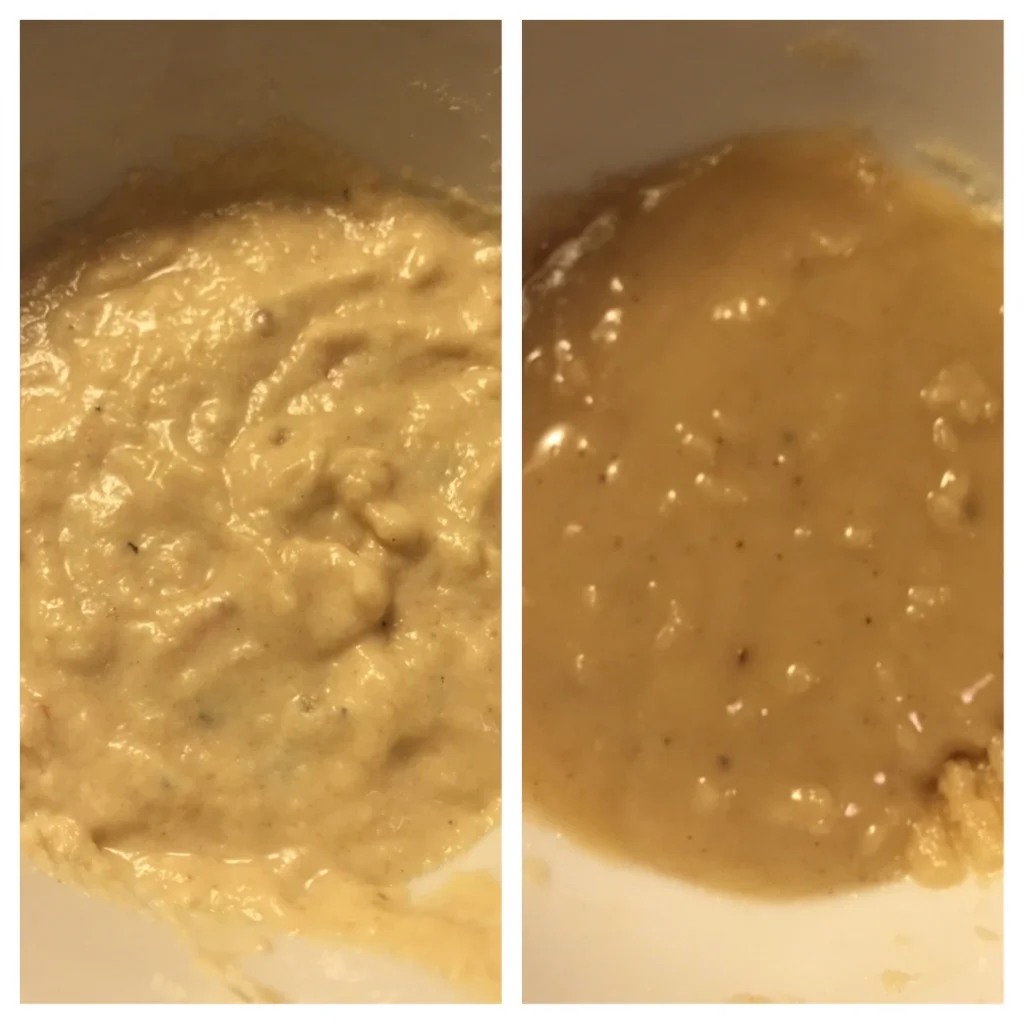

Simple. You make mixtures of flour and liquid that rival our bean paste for the least attractive award; but why the mixing? When flour is added in one starchy mass, it instantly begins to glue to itself and cause large clumps. If we suspend it in a separate liquid, we more evenly distribute its starch granules so it can create a significantly smoother product.

First to the plate was the lighter paste on the left, made simply by mixing my hot cooking liquid with flour to create an on-the-fly thickening tool. By adding a small amount and bringing my soup to a boil, it thickened within mere seconds. I had similar luck with my second mixture of flour and the residual bacon fat I drained at the beginning of the recipe.

There was no doubt that roux would have been my best bet in those key fleeting minutes at the end of the competition, but which one? Serving both to willing taste testers revealed that both were good, but the bacon fat mixture added an inherent meatiness to each bite without masking the flavors of the vegetables like the canned tomatoes had.

Just like that folks, we had a clear-cut winner: chili with bacon fat roux. Learn from my mistakes, breathe it in, in all its glory; oh, and take the recipe while you’re at it:

Fire-Roasted Vegetable and Apple Cider Chili (Fight Club Edition 2.0)

Serves 8

3 poblano peppers

5 Roma tomatoes

4 strips bacon, cut into 1/4 inch strips

1/2 pound lean ground beef

1 onion, peeled and diced

1 (12-ounce) bottle hard apple cider

1 (15-ounce) can dark red kidney beans, drained and rinsed

4 cups chicken stock

2 tablespoons Dijon mustard

Flour, as needed

Kosher salt and fresh ground black pepper

Place the peppers and tomatoes directly on the eye of a gas burner, turning occasionally, until completely charred (if using an electric stove, the same process applies under a high broiler). Transfer to a large bowl and cover tightly with plastic wrap.

After a few minutes, remove the veggies from the bowl, and using a paper towel, remove most of the charred skin (a little leftover is totally fine). Remove the seeds from both the peppers and tomatoes, dice, and set aside.

Place the bacon in an even layer in an unheated Dutch oven or large soup pot. Cook undisturbed over medium low heat until most of the fat has been rendered and the bacon is crispy on one side. Stir to allow even crisping, then transfer the cooked bacon to a paper towel-lined plate. Drain the excess bacon fat into a bowl and set it aside.

Raise the heat to medium and brown the ground beef in the remaining bacon fat. When evenly brown, transfer the beef to a plate and set aside.

Put the onions into the now empty pot and cook until translucent, then add the reserved peppers and onions. Stir to coat evenly in the fat, then carefully add half of the apple cider.

Allow the cider to reduce by half, then add the kidney beans and chicken stock. Bring the mixture to a boil, then lower the heat to medium-low and allow to simmer for at least 20 minutes.

Whisk flour into the reserved bacon fat until it forms a thick paste. Bring the soup to a boil, and add the mixture by the teaspoonful, whisking constantly, until a desired thickness is reached.

- Return the ground beef to the pot and add the Dijon mustard and remaining apple cider. Season the chili with kosher salt and black pepper. Serve topped with reserved crispy bacon.

Brand new to Chicago, Milo Klos received both his BA in creative writing and his culinary certification from the University of South Carolina. He taught cooking classes for a couple of years in a classroom kitchen in SC, but recently decided to move to Chicagoland to study baking and pastry at Le Cordon Bleu. Currently working as a private chef here in the city, Milo enjoys unwinding from a long day with a slice of pizza and anything even remotely Batman related.